Focus On Nursing

Focus On Nursing: A High Demand, High Growth Job of the Future

If you’re looking for a job in the future, then nursing is one of the strongest candidates out there. Although some aspects of the role may be susceptible to automation—in Japan scientists have developed a robot that can hand out medication and collect records—the central importance of empathy and advanced motor skills to nursing jobs makes it highly unlikely that machines will be replacing humans at our bedsides any time soon.

But that’s not all: According to the 2014 U.S. Census Bureau report, by 2050, the number of U.S. residents aged 65 and over is projected to be 83.7 million. As the population ages, there will be ever greater demand for healthcare professionals of all stripes, including nurses. And unlike many other fast-growing “jobs of the future,” the doors of a nursing career are open to those without a college degree.

But there’s a flip side, one that’s all too familiar to employers. As demand for nurses rises, the supply of qualified candidates does not always keep up, with the result that the U.S. faces a nursing shortage. So what is to be done? To get a deeper insight into the situation, we spoke with Dr. Joyce Knestrick, president of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners and an Associate Professor of Nursing at Georgetown University.

Although it’s a convenient shorthand to talk about “nursing,” the reality is that this is a rich and diverse field.

“That’s one thing I love about the nursing role—that there are so many different opportunities,” says Dr. Knestrick. “I think younger people aren’t necessarily aware of all of the opportunities within the field,” she adds.

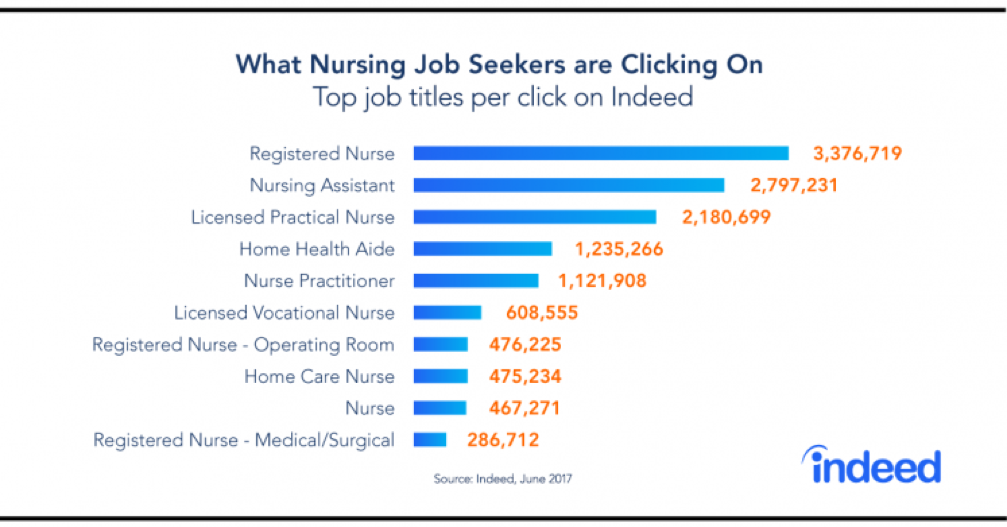

Thus, while demand is high for registered nurse (RN) roles (projected to see an impressive 16% growth through 2024, according to the BLS) there are many possible specializations.

For instance, Dr. Knestrick cites roles in management, nursing administration and nurse practitioner roles (these are nurses with an advanced degree who combine clinical diagnostic and treatment expertise with an emphasis on illness prevention). Then there are pediatric, neonatal, psychiatric, mental specialists and women’s health nurse practitioners.

And this is not to mention the nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives or people working in nursing informatics, who combine health science, computer science and IT skills to manage large amounts of patient care data. The possibilities—if not quite endless—are wide and varied.

“There’s a lot of room for advancement in the advanced practice roles, but I think even for the bedside nurses, there are opportunities. There are so many varieties that people can really find their niche in nursing as a career,” says Dr. Knestrick, who points to her own background as an example.

She started her career practicing for a long-term nursing care facility with a primarily geriatric population. Then she worked in a large tertiary care hospital on a medical-surgical unit, followed by a stint in critical care, before going on to become a nurse manager in pediatric and medical-surgical units, and then teaching in a diploma school of nursing. She has now been a nurse practitioner for 25 years.

Exploring the nursing shortage

Yet although nursing is a high demand, “future proof” field with lots of room for professional growth, the shortage remains a serious issue at present— and is likely to remain so in the future. Says Dr. Knestrick: “According to most of the information I’ve seen about registered nurses, I believe that we’re still going to see a shortage.”

And of course, a shortage of RNs will later translate into a shortage of nurses with more advanced qualifications.

A big part of the problem is that while the aging population may be creating opportunities for healthcare professionals, today’s nursing workforce is also aging.

“The average age of a nurse is around 50,” says Dr. Knestrick. “It’s estimated that over 50% of nurses that are practicing are over the age of 50. This means that within 10 to 20 years they will be retiring from nursing, which will further add to the shortage.”

In fact, the Health Resources and Services Administration predicts more than one million registered nurses will reach retirement age within the next 10 to 15 years, leaving a significant number of jobs to be filled.

This represents not just nurses needing to be replaced, but also a significant loss of knowledge and expertise. As a result, not only do hospitals need to find lots of new nurses, but they need to facilitate the transfer of invaluable nursing wisdom before it is lost.

But here’s another problem: there is also a shortage of nursing teachers to prepare the next generation.

“In some cases, schools have turned down nursing applicants mostly because of the faculty shortage,” says Dr. Knestrick.

What is to be done?

In some states, there are already strategies in place to address the shortage of nurse educators. For instance, the Nurses for Wisconsin initiative provides fellowships and loan forgiveness for future nurse faculty who agree to teach in the state after graduation.

Meanwhile, some nursing schools have formed strategic partnerships to help boost student capacity. For instance, the University of Minnesota has partnered with the Minnesota VA Health Care System to expand enrollment in the schools’ Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing program.

These programs could help with the teaching shortage. But what can employers do?

1) Stress the purpose and potential of a nursing career

In an age when many people are seeking meaningful work, one strategy for attracting new talent is to highlight the social value of nursing and the wide variety of available career paths to candidates.

“They should know that nursing is a wonderful profession,” says Dr. Knestrick, “that there are plenty of opportunities. There will always be sick people and they are always going to need somebody to provide care for them.”

2) Don’t overload nurses

Hospitals seeking cost efficiencies may be tempted to increase the workload on nurses—but this increases the risk of burnout and can make the existing talent shortage worse, says Dr. Knestrick.

A European study of acute care hospitals found that a greater proportion of professional nurses at the bedside is associated with better outcomes for both patients and nurses—thus reducing the risk of staff turnover. So it’s vital to look closely at staffing patterns, and staff accordingly.

3) Talent may be available in other areas

Another option is to recruit nurses from different parts of the country, as demand varies according to geographic areas, says Dr. Knestrick.

Some estimates even project nursing surpluses in some Midwestern states such as Illinois and Minnesota, while states such as California and Colorado will see nursing shortages.

With the correct incentives, it may be possible to target nurses in areas with greater supply and recruit them to areas where demand is more difficult to meet.

4) Make it easier for nurses to acquire—and practice—advanced skills

Employers needing nurses with more advanced qualifications could help provide programs to help them get the masters or doctoral level qualifications needed to become nurse practitioners, says Dr. Knestrick. But there’s another important step, too. Currently, many states place limitations even on nurses with very advanced skills, forbidding them to practice without another healthcare professional in place, thus limiting the extent of the care they can provide their patients.

Many of these rules were written decades ago, says Dr. Knestrick, and don’t reflect current conditions. She recommends that employers “support changes in nurse practice act to remove barriers for nurses, particularly nurse practitioners, to practice to the full extent of their license and their education is essential.”

Of course, enacting these steps and won’t end the nurse shortage immediately, but they are good steps towards ensuring that we don’t run short of these important professionals.

Content courtesy of Indeed

More on bsn jobs

How Can I Get Into a U.S. Nursing Degree as a Foreigner?

The demand for qualified nurses in the United States continues to grow, making nursing an attractive career path for students from around the world. If…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

WHY EARNING A BSN IS WORTH IT

Why Earning a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) Is Worth It—Especially at Sumner College Nursing has always been a calling, but today it’s also a…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

A BSN From Sumner College

Begin Your Nursing Career with a BSN from Sumner College in Oregon If you're looking to start a meaningful and rewarding career in nursing,…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Meet Teresa: Sumner College Graduate

Associate Degree in Nursing Teresa, congratulations on your graduation! As you’ve embarked on your nursing journey, remember: ‘Nursing is not just a profession, it’s a…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Meet Ana: Sumner College Graduate

Congratulations, Ana! Your hard work, heart, and perseverance have brought you to this incredible milestone. As you begin your journey in nursing, remember: “Nursing is…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Meet Misty: Sumner College Graduate

Associate Degree in Nursing Misty, congratulations on your graduation! As you’ve embarked on your nursing journey, remember: ‘Nursing is not just a profession, it’s a…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

AI in Nursing: A Trial

AI Note-Taking Tool Gives Nurses More Time for Patients at East Lancashire Hospitals In a forward-thinking move to streamline healthcare and reduce administrative burdens, East…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Bend Health Fair

Thank you to all who stopped by to say hi at the Bend Health Fair! What a great weekend! Have additional questions? Send us a…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

New Start, May 12!

Congratulations to our newest BSN cohort starting class on Monday in both Portland and Bend! Your new adventure awaits at Sumner College, Dream it Do…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

How Learning Style Impacts You

Welcome to “Understanding Your Learning Style” Unlock Your Academic Potential by Discovering How You Learn Best Have you ever wondered why some study methods work…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

RN Wages

A recent survey conducted by Incredible Health found that registered nurses (RNs) in Oregon earn an average annual salary of $98,630, or approximately $47.42 per…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

TEAS Exam Time!

The TEAS exam is a vital part of the admissions process and an important step toward your future in nursing. To help you prepare, we’ve…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

This week’s Information Sessions

Head over to one of our campuses for a great info session this week! In these sessions, you’ll learn about the application process, including how…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Changing the Nursing Narrative

The American Nurses Enterprise (ANE- associated with American Nurses Association) has launched a bold new initiative aimed at redefining how society understands and measures the…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Information Q&A

🌟 Discover Your Calling in Healthcare – Join Our BSN Info Session! 🌟 Sumner Nursing College | Bachelor of Science in Nursing 📅 Classes Begin:…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Information Sessions

Are you ready to take the next step toward a rewarding career in healthcare? At Sumner College, we are committed to providing you with the…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Bend, in May!

Take a sneak peek into one of our brand new classrooms at our Bend campus, on campus information sessions are held once a week, register…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Sumner College Student of The Month | February 2025

Congratulations Josephiene for being the February 2025 Student of the Month at Sumner! CONGRATULATIONS ON YOUR ACCOMPLISHMENT! Meet Josephiene, a dedicated nursing student whose passions…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

TEAS Exam Time!

The TEAS exam is a crucial part of the admissions process and a key step toward your nursing career. To help you prepare, we’ve gathered…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Nursing in Oregon

Become a Nurse at Sumner College Nursing School in Oregon! Ready to start a rewarding career in healthcare? Sumner College Nursing School offers a…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

International Women’s Day

Thank you to all of the women in our lives, including the majority of our nursing occupations!…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Apply Today!

Ready to start your nursing career? At Sumner College Nursing School, we offer hands-on training, personalized support, and a pathway to success in the healthcare…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Become a Nurse!

Nursing offers numerous advantages, making it a rewarding career choice. The profession boasts excellent job security, with a projected 6% growth rate among registered nurses…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

First Day!

Happy first day to our latest BSN cohort, and welcome to the Bend campus!…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Is Nursing School for Me?

Nursing school is not just an opportunity to build a rewarding career; it’s a chance to make a real difference in people's lives every day.…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Bend Countdown!

Welcome to Bend! We are excited for our first Bend BSN Cohort to start! Feel free to contact us with any questions!…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Studying for the TEAS Exam

As part of the admissions process, the TEAS exam is an important step toward your future in nursing. We've compiled a list of helpful resources,…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

What Kind of Nurse Should I Be?

There are many different kinds of nurses, some you may not know had a specialty, including: Case Management, Neuroscience, Telephone Triage, and Forensics. Regardless of…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

17 Days until Bend Launches!

With just 17 days until our first class of BSN's start in Bend, be sure to reach out to our admissions representatives to get all…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn

Helpful Hints!

Nursing students often face a variety of challenges, from long study hours to the financial strain of tuition. The coursework and exams can be intense,…

Share at FacebookShare at TwitterShare at PinterestShare at LinkedIn